Writing Home

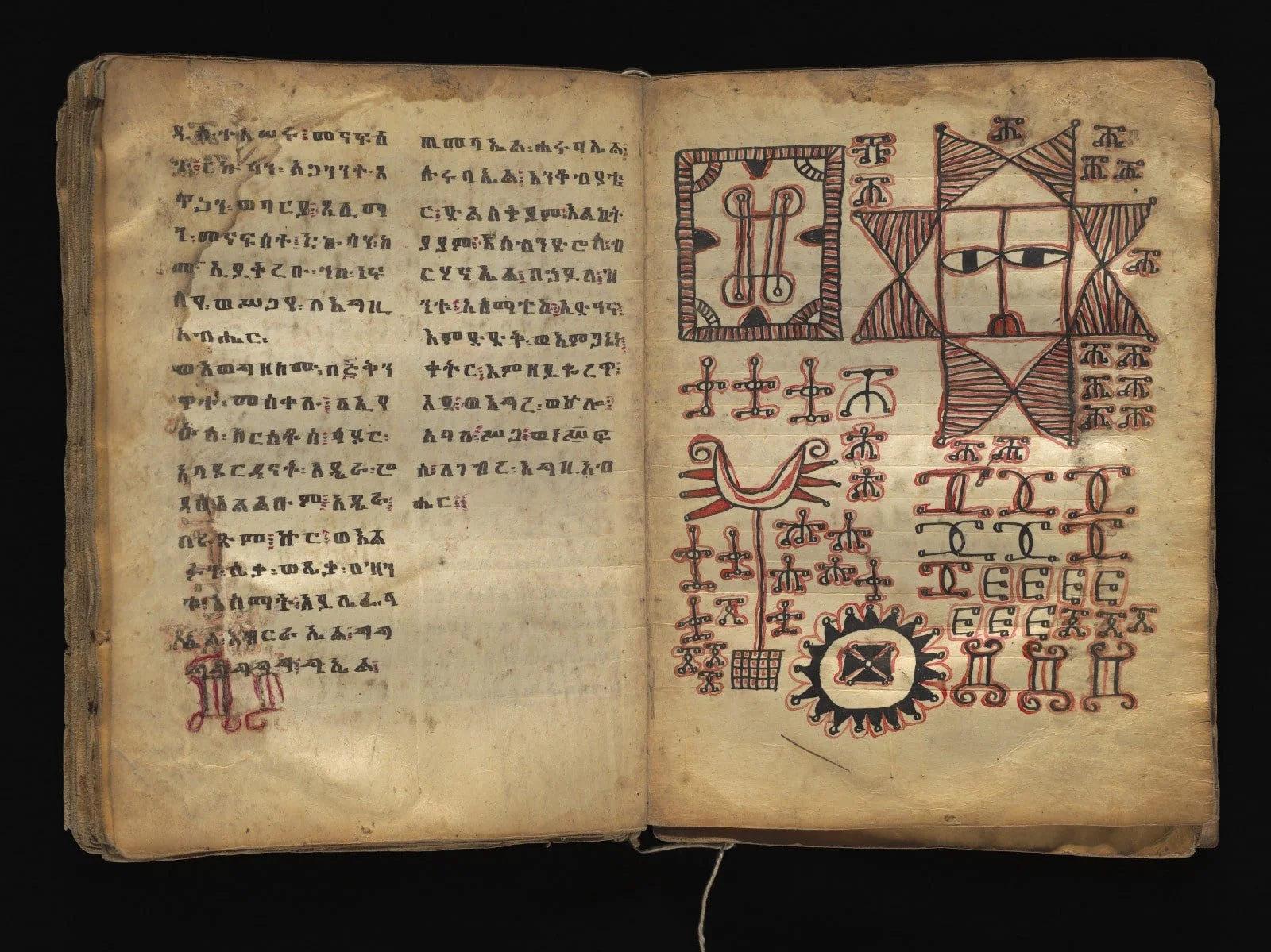

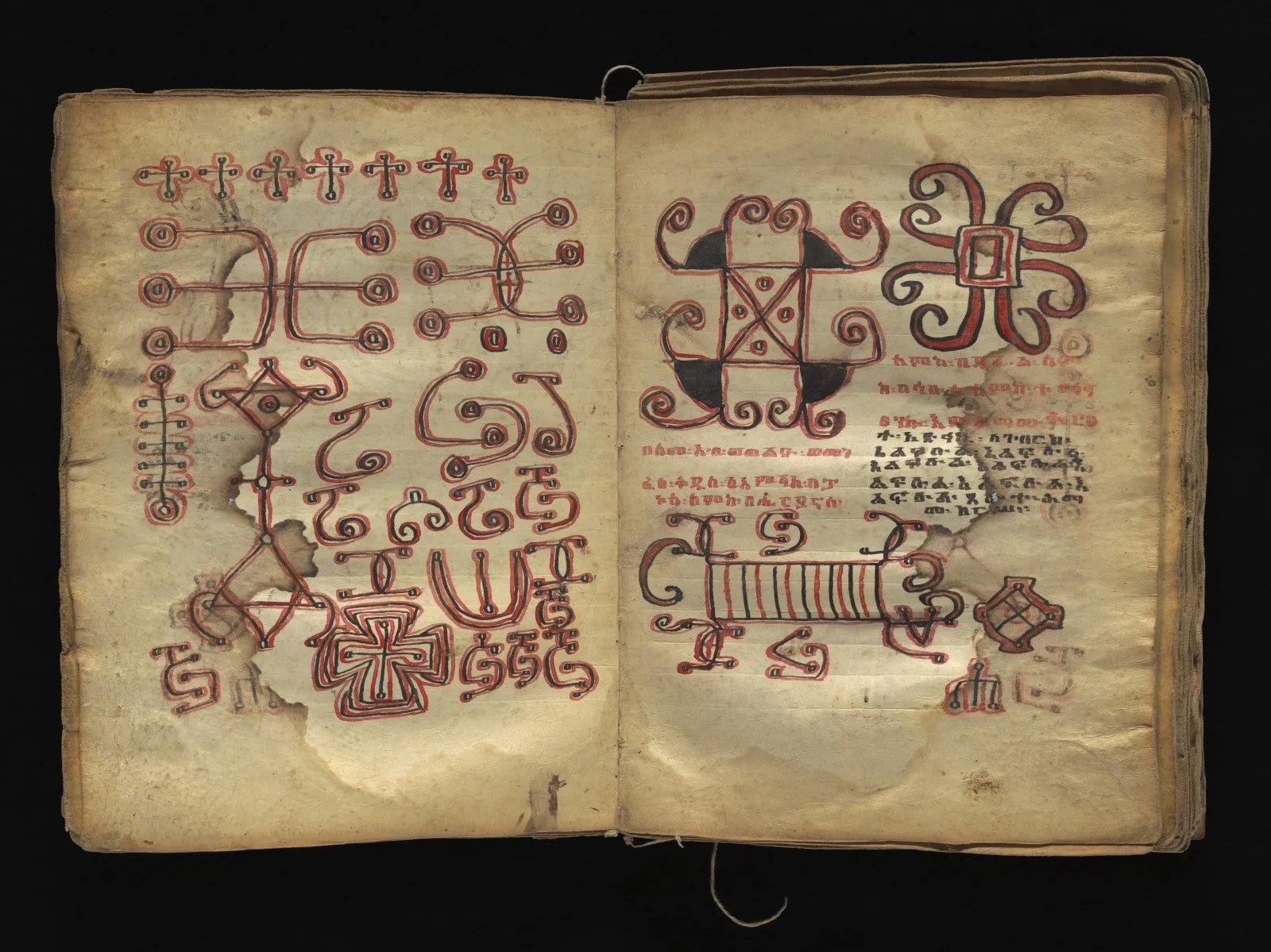

Book of Prayers and Talismanic Drawings, 19th c.

Ink on vellum, 32 leaves | page size: 7 ½ x 5 ¼ inches (19 x 14.5 cm)

Dabtara(s) name(s) not recorded, Ethiopia

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA

Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2016.232

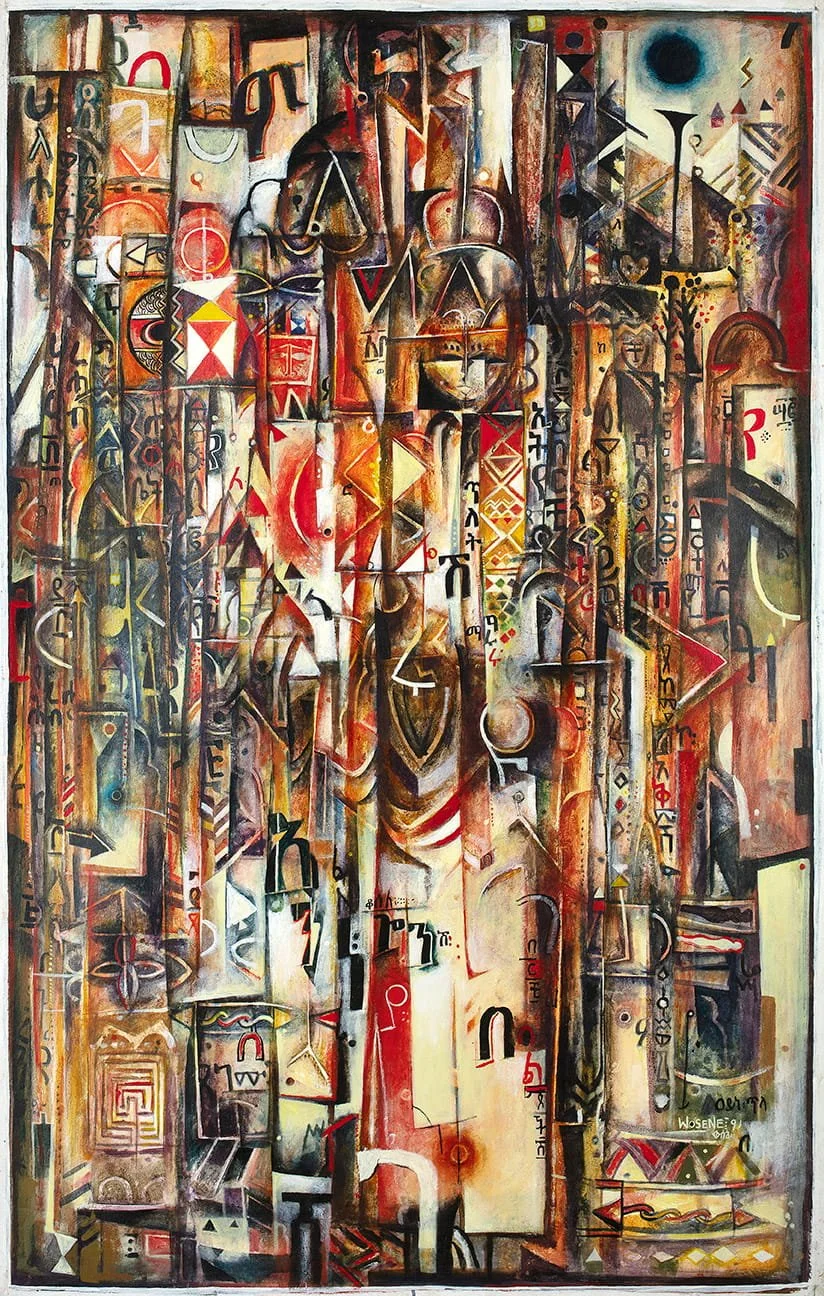

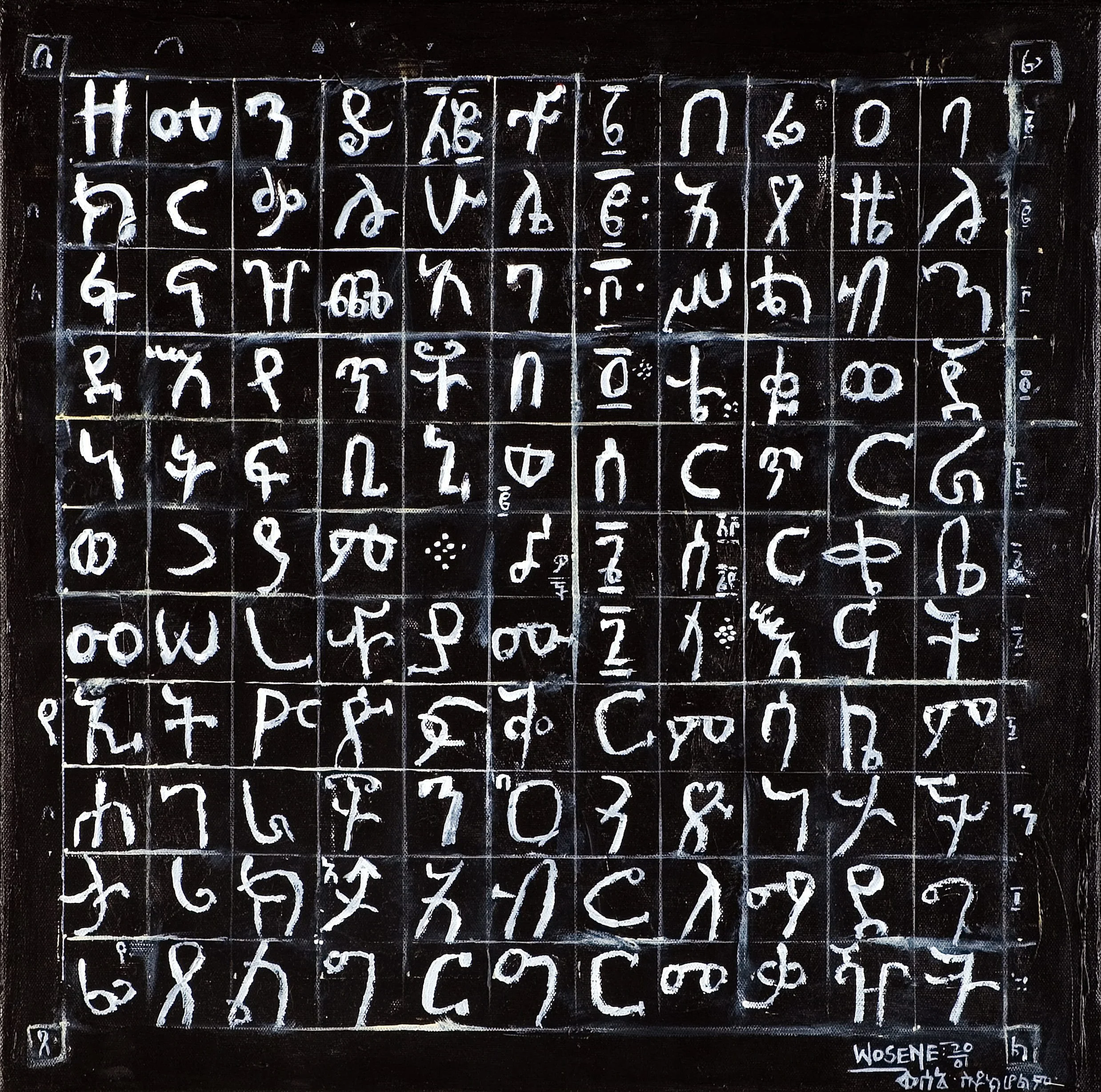

While learning the Amharic “alphabet” in school, young Wosene surely had no idea that the fidäl (Amharic’s more than 220 “letters”) learned in those lessons were treasures he would mine as an artist years later. But script is both timeless and portable, and although Amharic script originated several thousand years ago, it is readily at hand wherever he might be. With paint on canvas, Wosene has turned it into a defining artistic device.

Through my works, Amharic script has moved beyond its Ethiopian boundaries to become a global visual language, an international narrative, our story.[1]

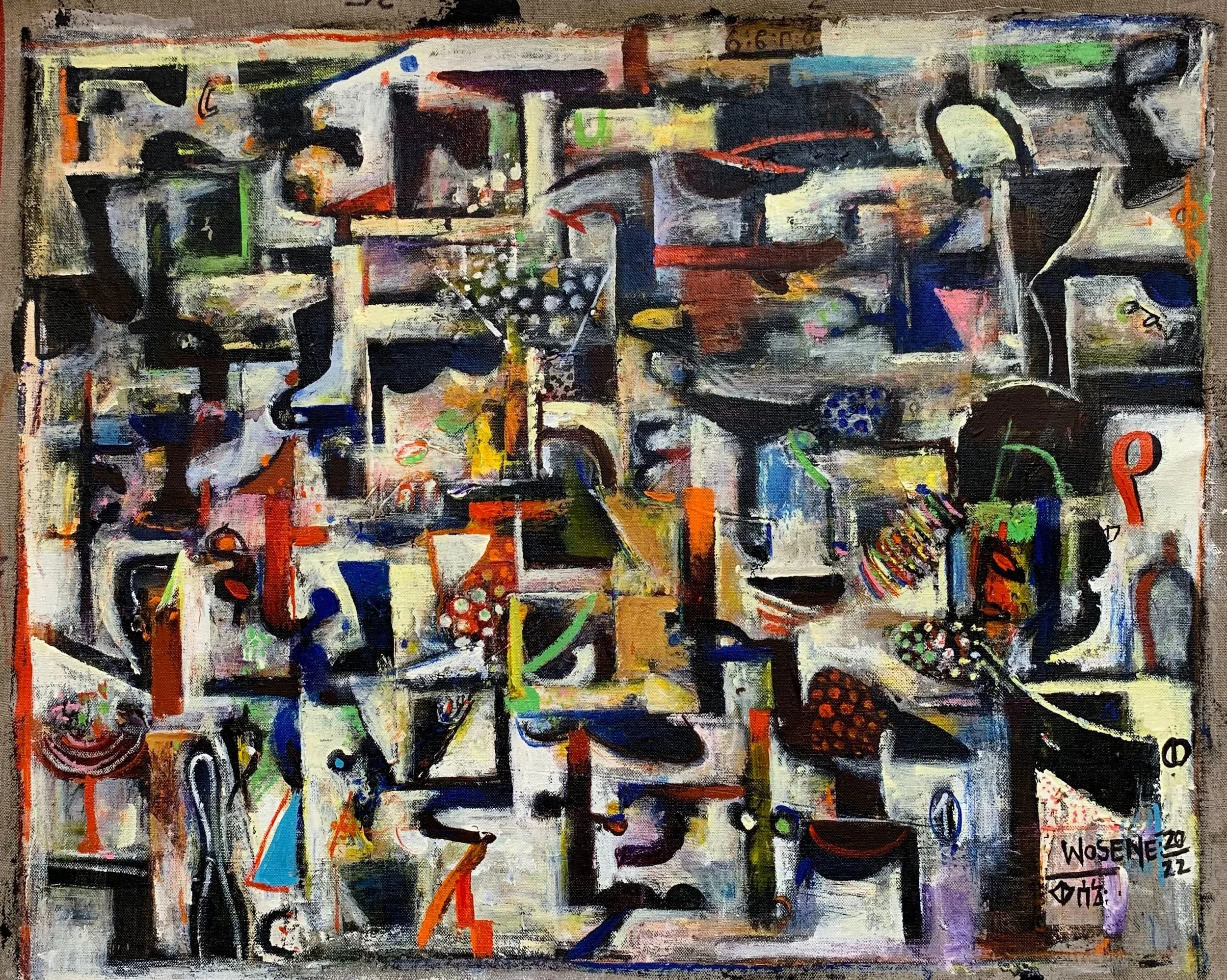

Wosene’s spontaneous process relies on “accident and intention,” triggering decisions to keep, change, or add to emerging forms in developing a composition. These unscripted conversations with paint are open-ended in a way that, to his mind, welcomes the viewer to join him exploring and questioning what he has done just the same as he “talks” back and forth with each developing work.

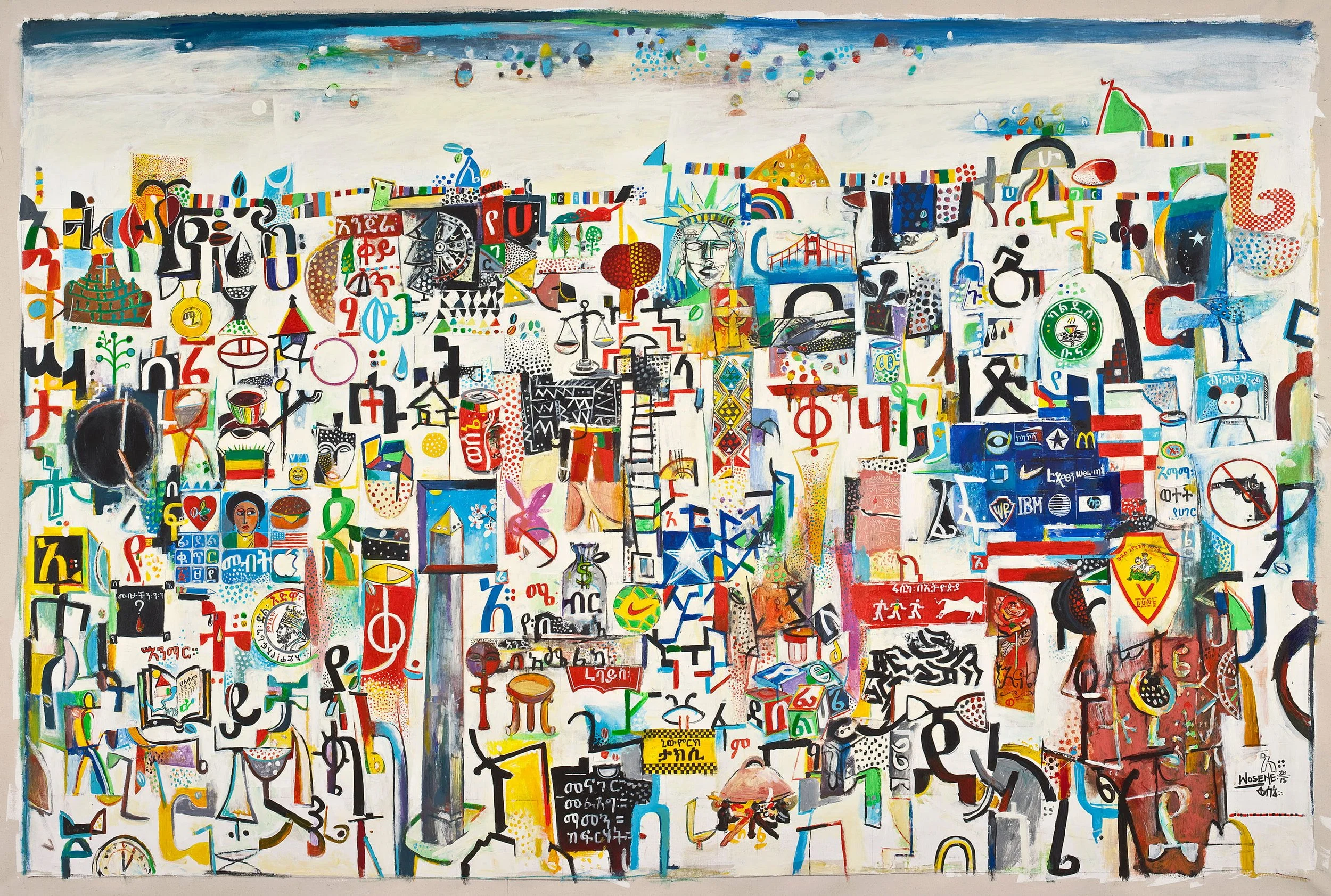

Through improvisation, Wosene opens up a free-ranging domain of expression in works that contain recognizable imagery and also those that are wholly abstract. In the large canvas My America II, 2015, the Washington Monument, Golden Gate Bridge, and Statue of Liberty stand among a host of American icons. Another well-known icon is transnational—the Coca Cola can—an American beverage here imprinted with Amharic letters. Tying this dense collage even more tightly to his homeland are a bottle of tej, Ethiopian homemade honey wine; coffee, a famous product of Ethiopia; the red, green, and yellow of the Ethiopian flag; and much more. True to Wosene’s approach, the work is spiced throughout with Amharic letters on products or standing out on their own. These linguistic traces reinforce the rhythm of mental moves brought on by the dazzling hopscotch of Ethiopian, American, and other international vignettes flickering across the surface of the canvas.

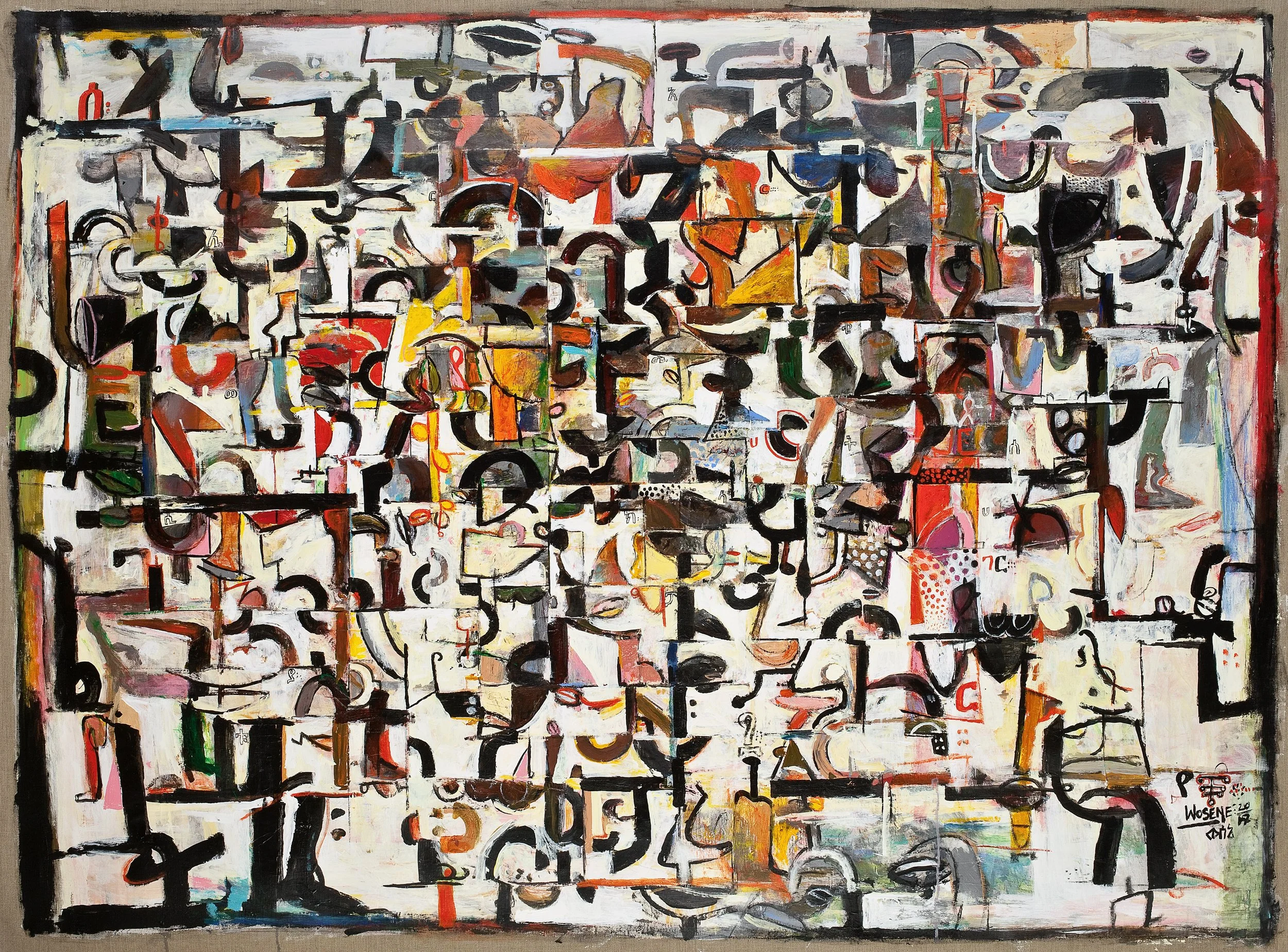

A painting of similar scale and visual power, Learning to Write X, 2017, also consists of a composite, collage-like structure. Here, powerful yet indefinite forms, largely in black, suggest unfinished letters. They create the impression of a nascent form of script cueing elemental sounds like the beginning of a language about to burst forth with power and clarity.

In both works, thin vertical and horizontal lines provide an indefinite and shifting grid reminiscent of an Ethiopian scribe’s delicate scoring of parchment to create faint lines for organizing the letters on a scroll or manuscript. In all of Wosene’s paintings, an Ethiopian presence resides in the filaments of Amharic script that he weaves into the compositional architecture. His manipulation of the shapes of letters, turning them into expressive devices, does not stray far from his experience growing up in Ethiopia where trained healers, called däbtära, inscribe modified letter forms, magical number sequences, diagrams, and supernatural beings on manuscript pages and scrolls in order to heal or protect their owner (see reference images below). Wosene’s personal familiarity with these text-based practices stems from his mother giving him a sash to wear that contained scrolls with verses and talismanic drawings to protect him from illness and harm during his daily coming and going.

[1] Excerpt from “Life as a Canvas” by Wosene Worke Kosrof, in AGNI 89 (2019) 139.