WordPlay

For me, (Amharic letters) are much more than elements linked together to generate words. They create a visual language in which each symbol becomes an elegant architectural structure, or a movement in a rhythmic dance . . .

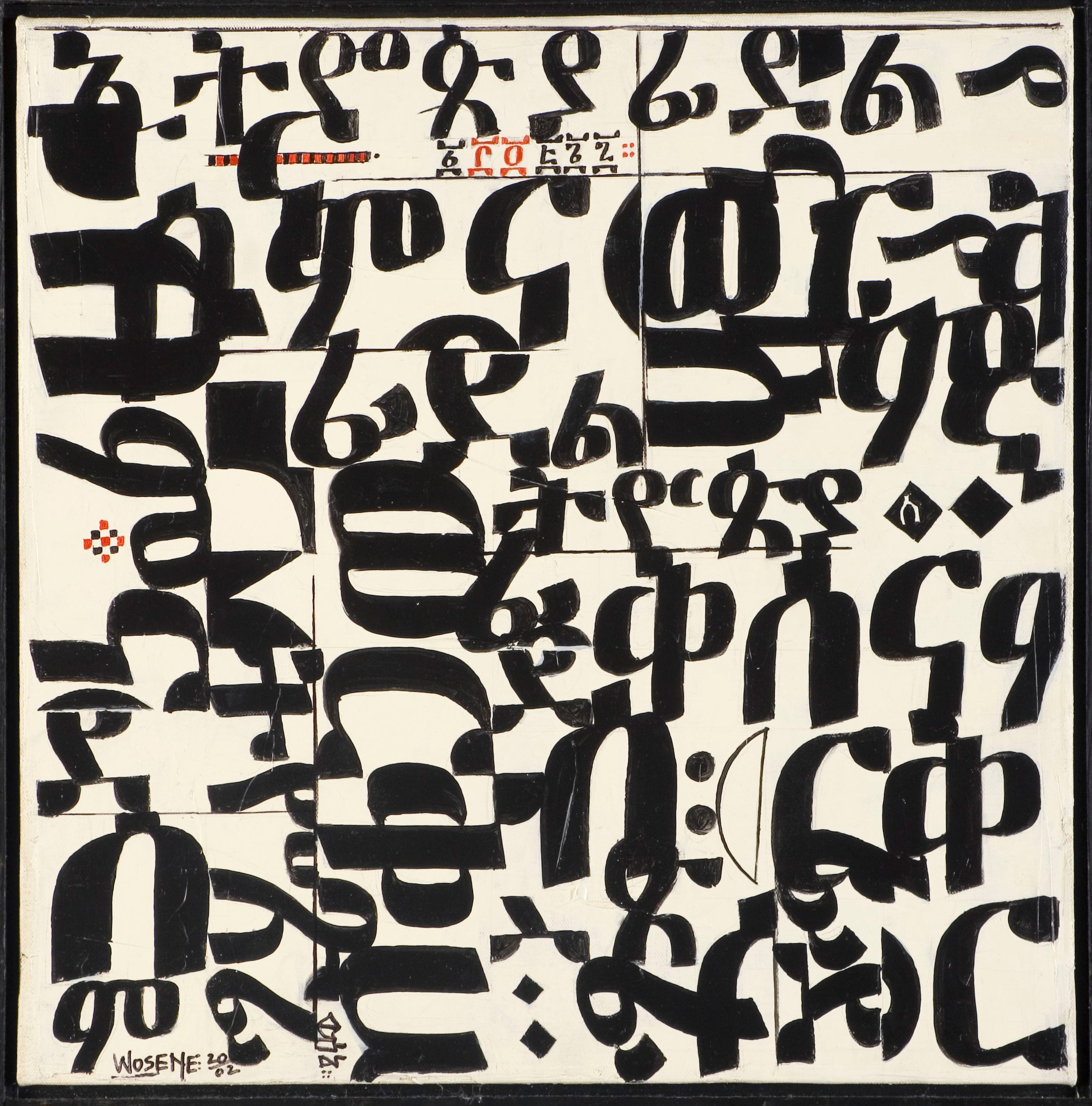

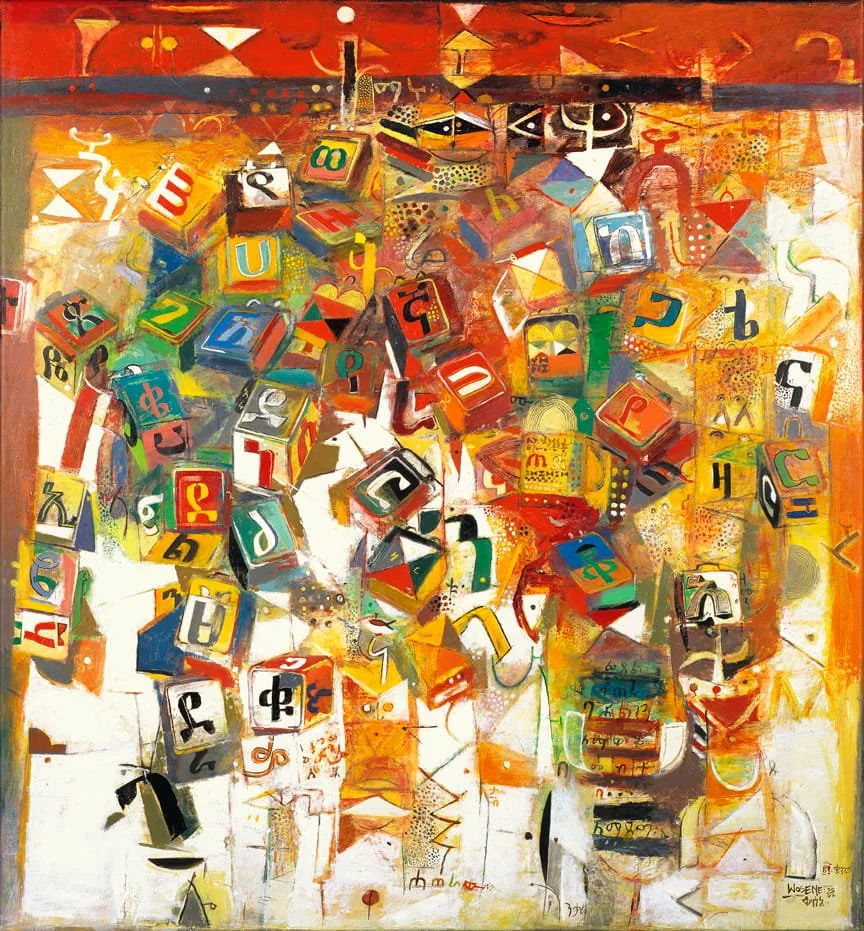

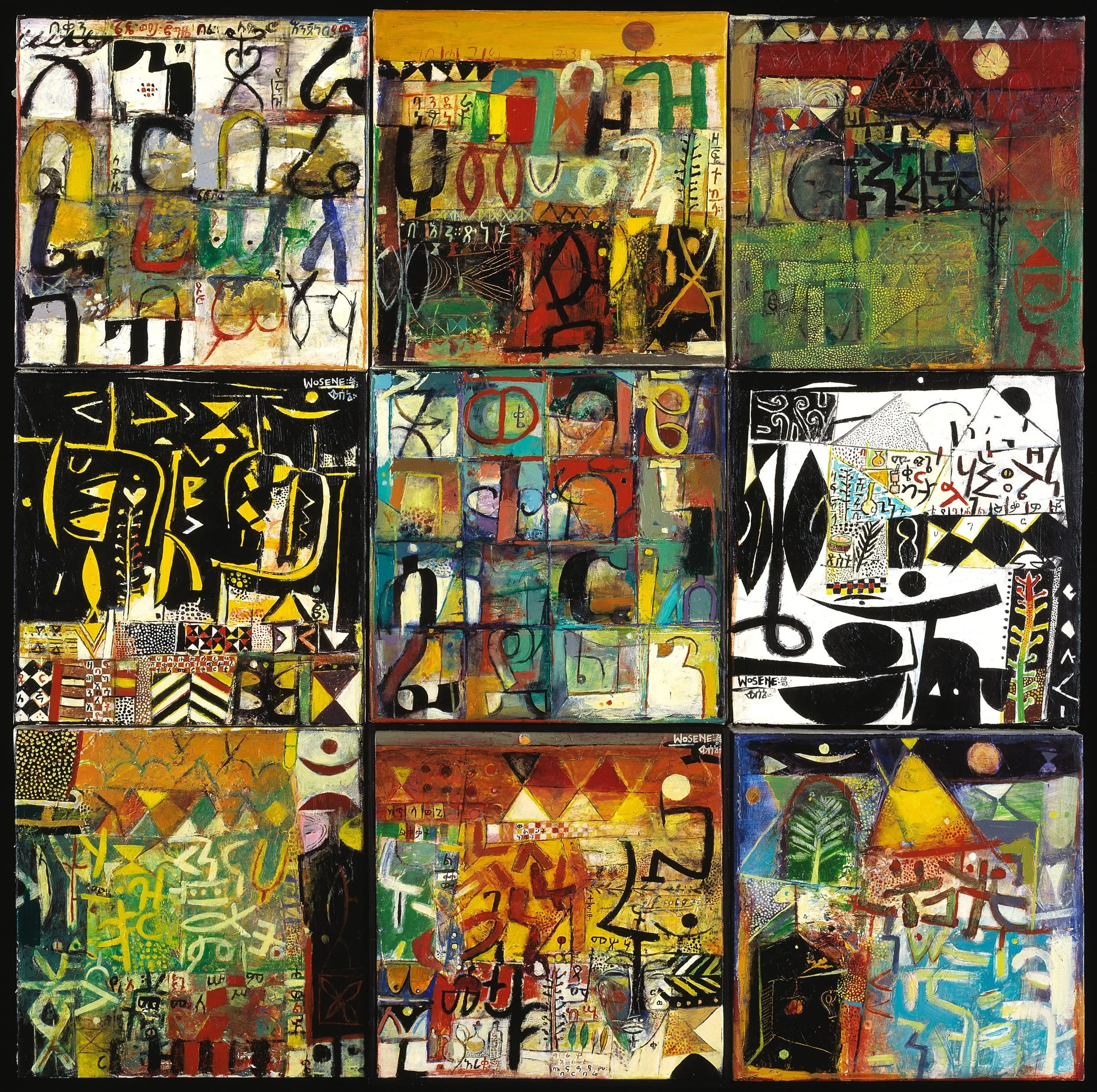

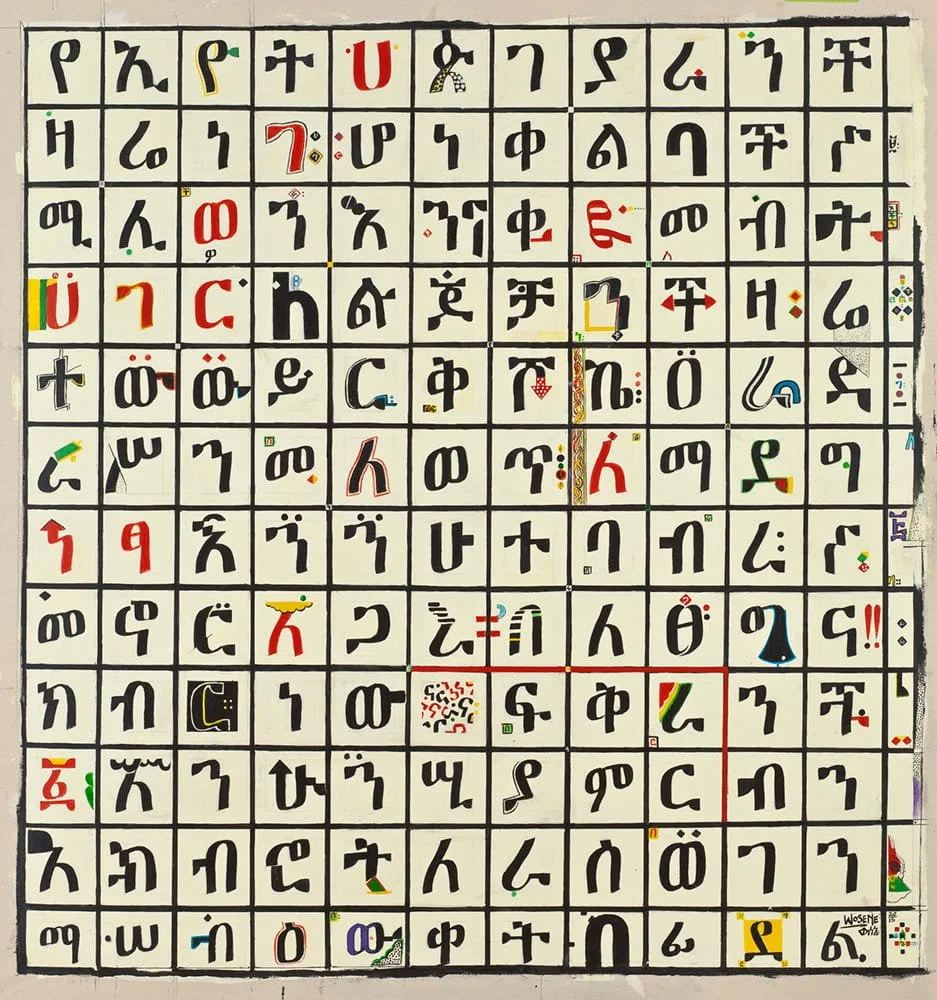

Called fidäl, Amharic “letters” combine a consonant and a vowel to represent a specific syllable of sound. The fidäl shapes (there are more than 220) fascinated Wosene as a child and have been a wellspring for his art.

After learning Amharic script as a very young child, at age six Wosene moved to a school where he learned English using Latin script. Thus, he was exposed to two different systems of abstract symbols for spelling the words and representing the sounds of spoken and written language—Amharic script, where each character indicates a specific syllable sound that links with others to make a word, and the Latin alphabet where letters spell the words and the letter sounds vary according to their combination.

Wosene’s feel for the aesthetics of script was heightened at the School of Fine Arts, where he studied Ethiopic lettering with Yigezu Bisrat, a noted calligrapher who also designed Amharic typographic fonts. Then, at Howard University, Wosene studied with Jeff Donaldson, a member of AfriCOBRA, a group that fostered Afro-centric ideology and often employed letters and words to convey social messages and add aural dimensions to their paintings.[1] Chairman of the department and Wosene’s advisor, Donaldson stunned the new student when he recommended that he “go home,” until Wosene realized the suggestion was intended metaphorically to mine his personal experiences and identity. Amharic script provided him a matchless, deeply internalized avenue “home.”

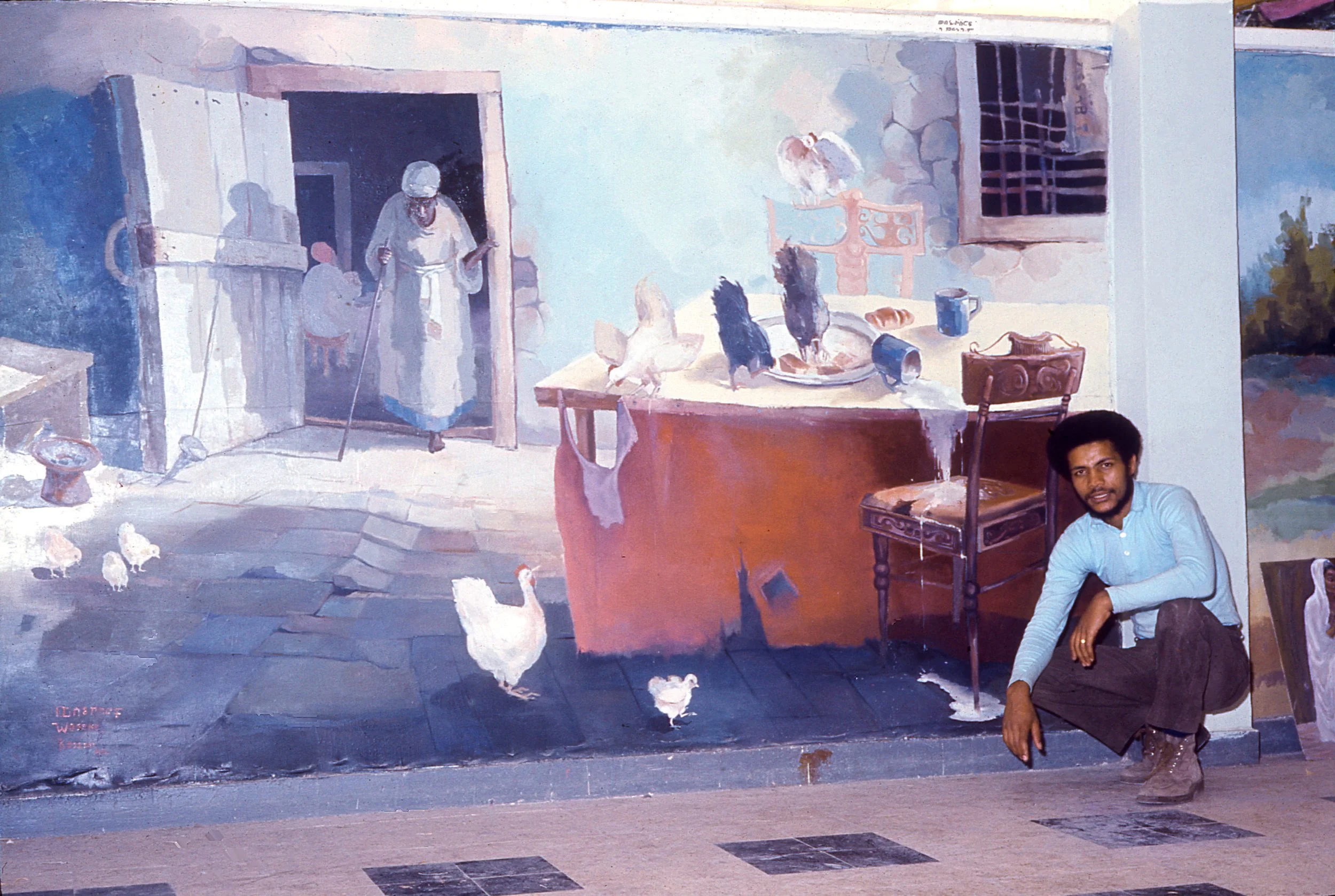

Wosene mentions feeling his way at first, seeking to show the beauty of script as an art form. In Mother and Child (1982), the mother, wearing a red head scarf, looks down as she cradles her nursing infant. The figures are enveloped in layers of script, some of which can be read and some that are letter-like echoes for design only.

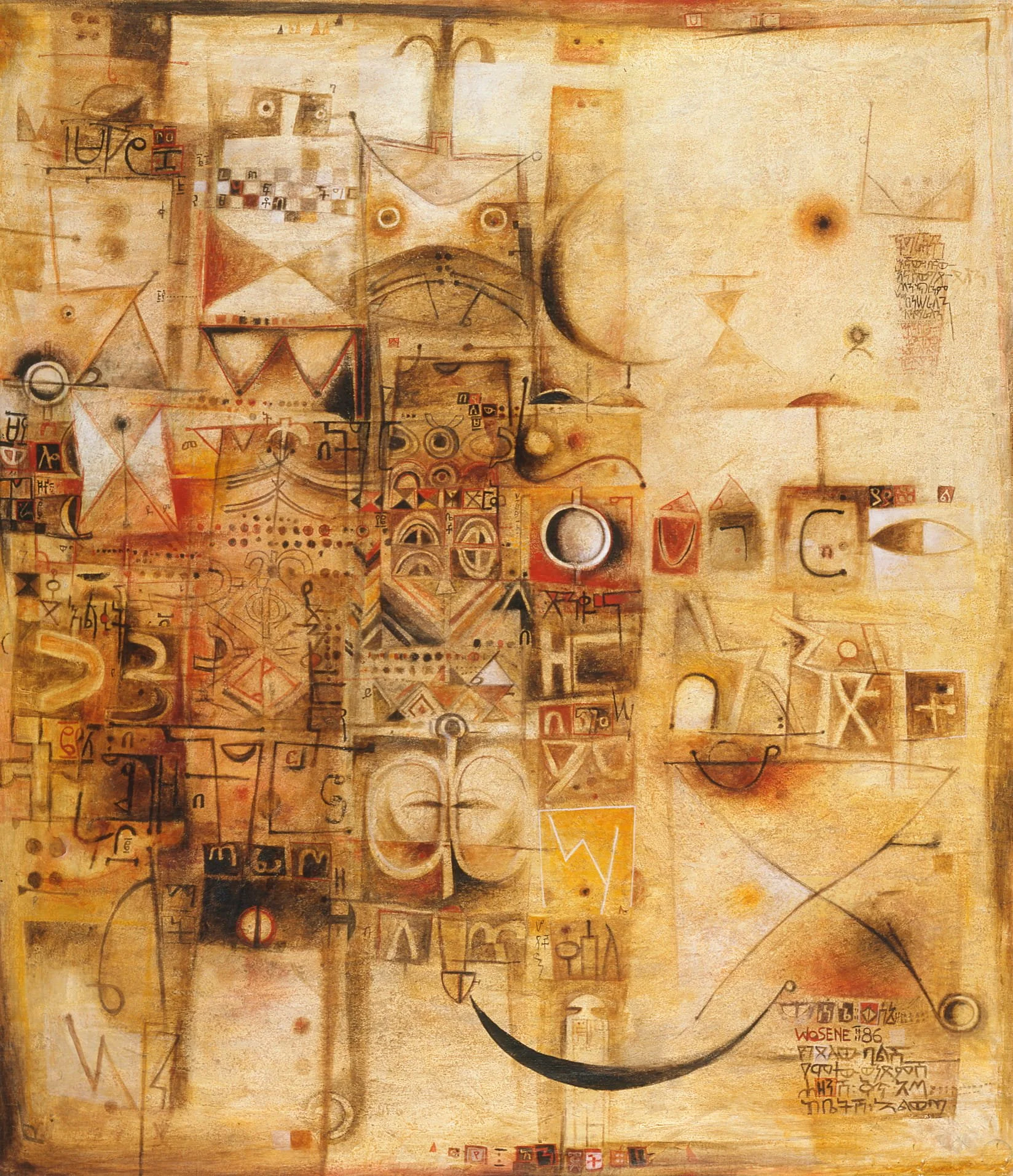

The experience of seeing graffiti on construction fences and subways in New York inspired Wosene to push the expressive possibilities of script even further. His composite view of the city in Lady Liberty (1986) reflects this experience with passages of graffiti in the lower half. The lacy, undulating lines for the cables of the Brooklyn Bridge that thread across the canvas reveal Wosene’s attention to linear designs by Sudanese artist, El Salahi that were inspired by Islamic calligraphy. Wosene also took an interest in the work of Jasper Johns and Jean-Michel Basquiat and other artists who were exploring the use of letters and words in their work.

As Wosene mastered the expressive capacities of Amharic script, he began to play with letter forms more daringly.

(I explore) their versatility and the playfulness of their surfaces and interiors, dissecting their skeletal structures, and observing how they move, interact, intersect. I hear them speaking to each other as I elongate, distort, and invert them . . .

Even when placing fidäl within the stability of a grid, Wosene plays with transformation. Each compartment in Words of Memory X (2015) presents a single fidäl. Most adhere to proper form, but even in this deceptively straightforward scheme he embellishes in and around the letters, morphing this character or that while toying with the grid as well. However, when a tightly structured painting like Words of Memory X is juxtaposed to a more monumental canvas like We the People III (2025), it becomes clear just how far Wosene has been able to push the aspect of “play” to intensify the expressive power of script, achieving the reach of a symphonic, if not epic voice.

Through my works, Amharic script has moved beyond its Ethiopian boundaries to become a global visual language, an international narrative, our story.[2]

[1] The African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA) was founded in Chicago in 1968 by Jeff Donaldson, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Wadsworth Jarrell and Gerald Williams.

[2] All excerpts from “Life as a Canvas” by Wosene Worke Kosrof, in AGNI 89 (2019) 131, 139.